Post Modern

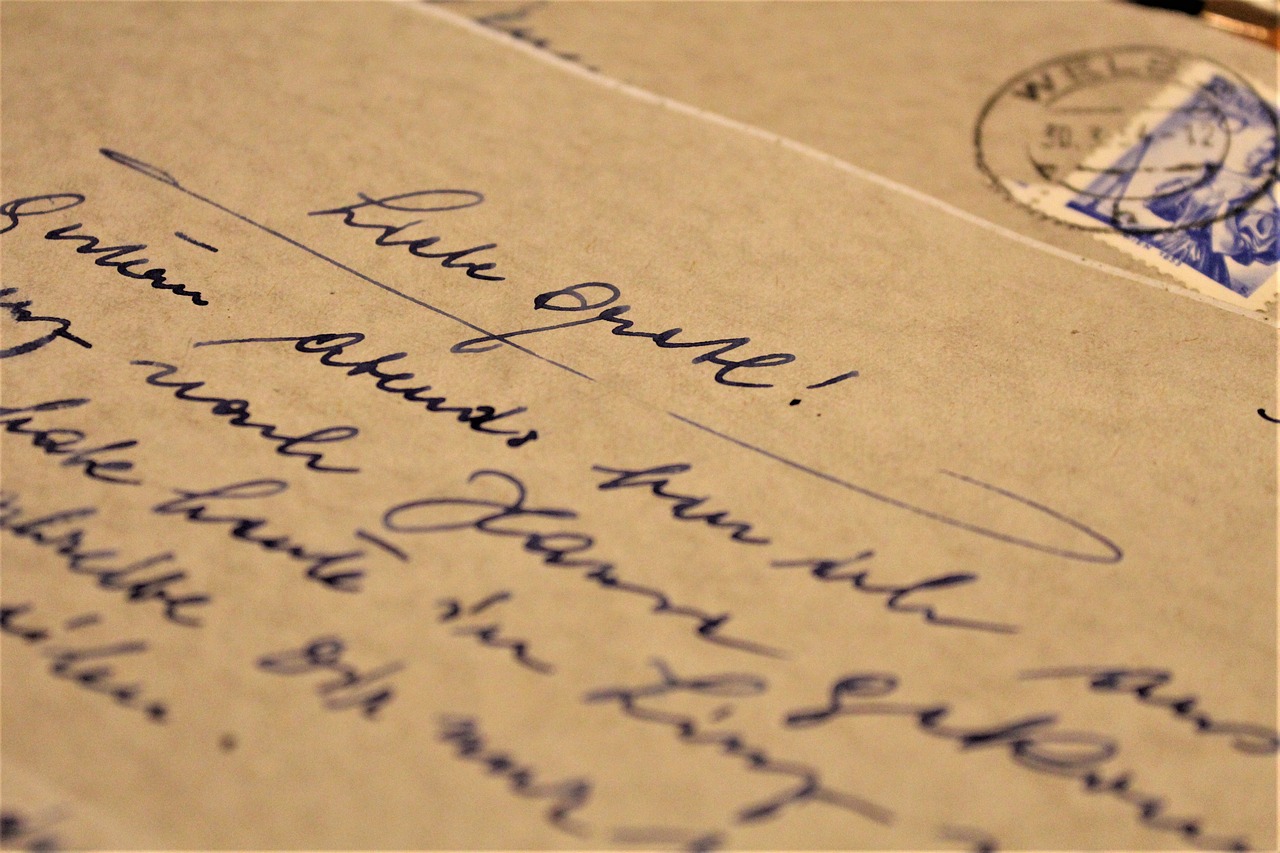

On the lost art of writing and sending a letter.

Often, the thud of mail through the front door is met with a sigh. If it isn’t an electricity bill, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime promotion from a discount furniture store or a flyer from the local pizza place. The online world—with its minefield of political fearmongering, spam links and jealousy-inducing vacation photos from acquaintances—doesn’t offer much more. Has the age of meaningful correspondence come to an end? And if so, what have we lost along the way?

The digital age has reformed both the way that we correspond and the means through which we can view others’ correspondence. With letters, we are permitted unregulated access into the inner musings and fluctuating emotions of the author. And because of their sentimental sway they are usually lugged from one home to the next, all the great hopes and heartaches of a lifetime collected in a shoebox and stashed under the eaves. Emails, however, are password protected, guarded by privacy laws and unlikely to be found in an attic. Even if people did consciously donate their digital archives, these exchanges lack the same emotional resonance.

“Personally, I love receiving letters, especially now that it’s so rare to get something through the post that isn’t junk mail,” says Simon Garfield, a British journalist and author of To the Letter: A Celebration of the Lost Art of Letter Writing. Tracing the significance of letter writing throughout history—we have, he notes, relied upon it to communicate for more than 2,000 years—his book celebrates the legacy of numerous historical correspondences, like the unfolding (and then failing) relationship between Napoleon and his wife, Josephine. “As someone who writes a lot of history, I don’t know where I’d be without archives and letters and the ability to track someone’s life and transactions through the written word,” he adds. “I don’t think we’ve become less communicative,” Garfield observes. “I just think the kind of depth and the lasting value of that communication through time has diminished.”

Much of our reluctance toward letter writing boils down to convenience. The immediacy of email, and the omnipresence of social media, has made the delayed gratification of writing and waiting for a letter feel antiquated. Then there are the practicalities to contend with: a stamp to buy, the trip to a mailbox. But imagine hearing that thud through the mail slot and discovering a handwritten missive lying on the mat. Most likely it would be relished far more, and preserved much longer, than the email which arrives with a ping.

“We write letters in a different way than we compose emails and texts,” Garfield continues. “They tend to take longer to compose, they tend to be better composed, and they have a beginning, middle and an end. We tend to dash off correspondence in a digital way far faster and with probably less imagination and perhaps more exactitude. They’re great for business transactions, less so for emotional correspondence.”

As letter writing falls by the wayside, Garfield has, ironically, found himself increasingly amenable to a form of correspondence usually met with derision: the annual Christmas letter. Long mocked by the likes of the late journalist Simon Hoggarts—who delighted so much in their bashing that he created The Round Robin Letters, an anthology compiling his favorites—the Christmas letter straddles an unusual fault line. Still a letter, but, like a Facebook status update, sent to a mass audience, it’s a tradition imbued with bragging rights and blow-by-blow accounts of life’s petty grievances. Yet even with their more distasteful aspects (Hoggart’s book includes news of cats opening fridges and hamsters that love Puccini), Christmas letters represent a strain of personal letter writing that Garfield worries is fast becoming extinct. “I feel warmer towards those things because, along with condolence and thank-you notes, they may be one of the last bastions to fall,” he says.

Originally from Kinfolk 29